LINSPECTOR: Multilingual Probing Tasks for Word Representations

Published:

This is a simplified blog post for our paper that will appear in the June 2020 Issue of Computational Linguistics Journal and will be presented in ACL 2020.

Introduction

Recent developments in deep learning has changed the NLP field and provided great improvements on many NLP tasks over previous statistical or rule-based models. However there was still one issue, as Mark Steedman said in his award talk in ACL 2018:

“LSTMs work in practice, but do they work in theory?”

—it was before the Transformers era, when majority was still using LSTMs for NLP, however the question still remains open for other models as well. The NLP researchers had based their models on linguistic theorems or insights, e.g., by means of incorporating linguistic features, developing parsers that conform to a grammar theory. The models were therefore interpretable and we had a sense of control over them. The lack of interpretability of so called black-box NLP models has led to establishment of another subfield, “Interpretability and Analysis of Models for NLP”. Some workshop series such as BlackboxNLP and Representation Evaluation (RepEval) are being organized at big NLP conferences; and starting from 2020, interpretability has its own track in top-tier NLP conferences like ACL 2020 and EMNLP 2020.

Close ties between interpretability and evaluation

Gaining insights about a model (i.e., interpretation or analysis) can be achieved via evaluating the model for the case of interest. For instance, one could be interested in whether the model has developed an understanding of semantic similarity, and create an evaluation task to test this ability, e.g., by checking the vector similarity between word pairs that have a certain relationship as in Mikolov et. al., 2013.

Main quantitative evaluation techniques for black-box NLP models

In scope of this work, we mainly group them under three categories: (1) vector similarity, (2) extrinsic and (3) via probing:

(1) Vector Similarity

This method relies on similarity benchmarks that typically consist of a set of words or word pairs that are manually annotated for some notion of relatedness (e.g., semantic, syntactic, topical, etc.). The most famous one is the analogy task, e.g., given a pair of words, “man” and “woman”, the task is to find a target word which shares the same relation with a given source word. For example, given a word “king”, one expected target word would be “queen”. The target word is found via simple linear vector operations. Pros: Once the benchmark is created, evaluation is simple since it does not require any training but only simple vector operations. Cons The consistency of the vector offset and the structure of the vector space model as discussed by Linzen, 2016 and Rogers et. al., 2017 make it less reliable. Also, the datasets are mostly manually curated, hence are not easy to create for low-resource languages.

(2) Extrinsic

This is the most common technique, where the models are evaluated on downstream NLP tasks such as named entitity recognition, semantic role labeling or question answering. Pros: For most researchers, the end task performance is the most important measure. Therefore, extrinsic evaluation gives a direct measure on the end NLP task, instead of an approximation. Cons: First, it may be computationally expensive—depending on the dataset size and the complexity of the task. Second, it can be considered a specific measure rather than a generalizable one, i.e., having a high performance on one downstream task, does not give any hints on its success on another downstream task. Hence it should be evaluated separately for each. In addition, there are many factors related to dataset statistics like dataset bias, playing a role in a model’s success in downstream task. Therefore, it is hard to distinguish whether the high performance is due to the model or other factors. This is definitely an issue for all evaluation techniques we consider in this post, however has the highest impact on extrinsic evaluation.

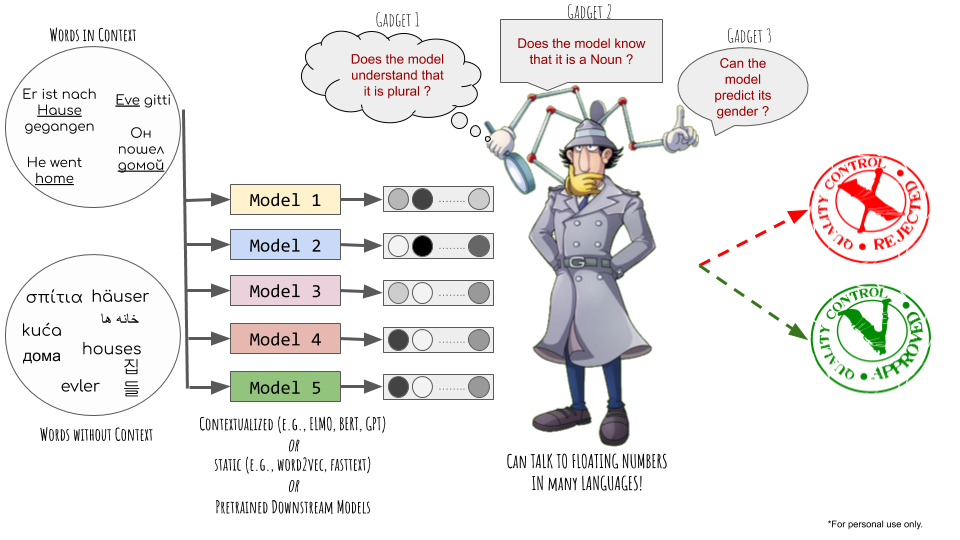

(3) Probing

Sometimes also referred to as challenge tasks, control tasks, auxiliary prediction tasks or diagnostic classifiers, probing tasks are a set of multi-class classification problems that probe a learned representation (e.g., word vector, sentence vector) for a single simple linguistic property such as “plurality/singularity of a word”. A more comprehensive definition of this approach is given in Belinkov et. al., 2019 as:

Typically, in this approach a neural network model is trained on some task (say, MT) and its weights are frozen. Then, the trained model is used for generating feature representations for another task by running it on a corpus with linguistic annotations and recording the representations (say, hidden state activations). Another classifier is then used for predicting the property of interest (say, part-of-speech [POS] tags). The performance of this classifier is used for evaluating the quality of the generated representations, and by proxy that of the original model.

Probing of NLP models has quite a history starting from 2010’s—(Köhn 2015, 2016; Shi et. al., 2016; Adi et al. 2017; Conneau et al., 2018; Tenney et. al., 2019 and also a more general survey paper by Belinkov et. al., 2019). Pros: It provides more focused insights regarding the linguistic properties that are captured by the learned representations, hence ideal for analysis. It can be considered a more general measure, i.e., high performance on one probing task, can be correlated with successes on multiple downstream tasks (e.g., a model that can predict universal word classes better, can be expected to perform well on syntactic downstream tasks). The complexity of probing tasks are generally lower than downstream tasks, hence less computational resources are required typically. Cons: It is not yet clear whether probing tasks are a good way to approximate a model’s success on downstream tasks due to the challenges in performing meaningful correlation studies. Although the probing classifiers are easier to train, one still needs to train a classifier which is more computationally expensive than linear vector operations as in intrinsic evaluation. Probing tasks also need probing datasets for training and testing—but obviously less effort for annotation as it is usually done automatically. Relying on a dataset comes with the risk of introducing undesired biases—as in other methods.

How can probing be of help?

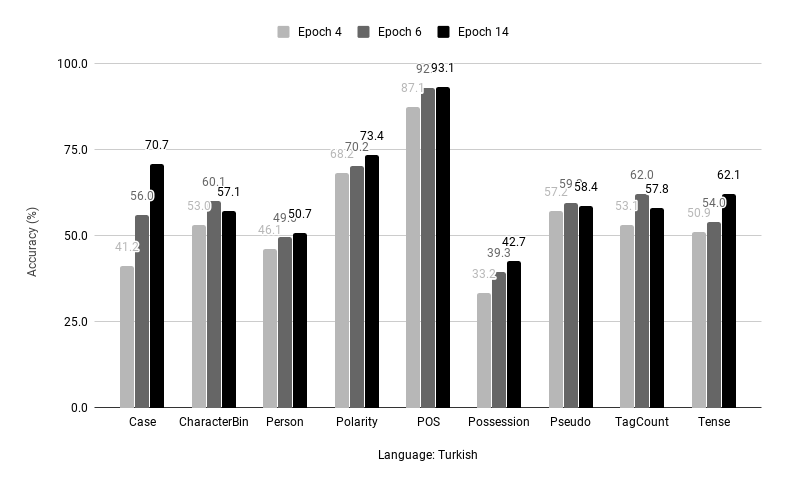

- Scenario 1 - Analysis: The most typical application scenario is where probing is used as a diagnostics tool. Imagine you have a pretrained downstream model and you want to gain insights on what the model has captured. Then you can probe different epochs or different layers of the model and analyze the changes of probing task scores. For instance, you can find out that the encoding layer of a Turkish SRL system gets better at “Possession” probing task during training as below.

Scenario 2 - Proxy: There are too many design choices for the model you’re implementing, e.g., from using cross-lingual, retrofitted, multi-sense or dependency-based embeddings to different subword unit choices (words, characters, character n-grams, morphemes, phonemes). You want to know how each decision will impact the performance of your dream downstream models. Then you can use the probing scores as a proxy to downstream ones, e.g., if character n-grams achieve higher scores on “Case Marking” task, then this design would probably lead to higher scores for syntactic and shallow semantic level downstream tasks like dependency parsing and semantic role labeling.

Scenario 3 - Comparison: Probing results may provide information on the “general” quality of the pretrained embeddings.

Why do we need “language-specific” probing?

Let’s start with a simple fact: languages are different, i.e., have different properties. However, as in other subfields of NLP, probing has also been dominated by English language. However, the information encoded by the word order and function words in English is encoded at the morphological, subword level information in many other languages. Consider the Turkish word katılamayanlardan, that means “he/she is one of the folks who can not participate”. In morphologically complex languages like Turkish, single tokens might already communicate a lot of information such as event, its participants, tense, person, number, polarity as in the example. In analytic languages, this information would be encoded as a multi-word clause. The languages also differ on what information they encode on word-level. For instance, while some languages contain “Gender” information, some don’t. Therefore multilingual probing tasks should take language-specific properties into account.

What do we do in this study?

We introduce a variety of type-level probing tasks, meaning words without context, for many languages by taking language properties into account. Our probing tasks cover a range of features: from superficial ones such as word length, to morphosyntactic features such as case marker, gender, and number; and psycholinguistic ones like pseudowords (artificial words that are phonologically well-formed but have no meaning).

We also introduce a set of comparable token-level probing tasks that employs the context of the token. We analyze the type- and token-level probing tasks through a series of intrinsic, extrinsic and diagnostic experiments.

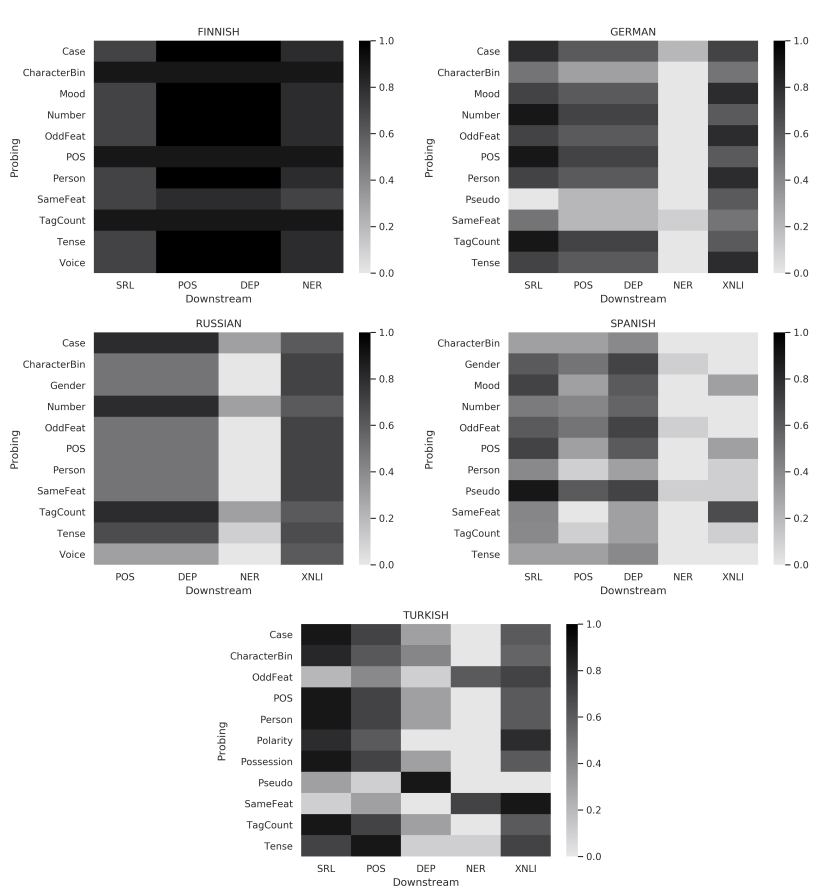

We statistically assess the correlation between probing and downstream task performance for a variety of downstream tasks (POS tagging, dependency parsing (DEP), semantic role labeling (SRL), named entity recognition (NER) and natural language inference (NLI)) for a set of typologically diverse languages.

Probing Tasks

We offer (1) morpho-syntactic and morpho-semantic tasks (e.g., universal pos tag, case marking, gender, tense, number etc…), (2) pseudo-word task (3) comparative tasks (e.g., finding the common or odd linguistic feature given two forms) and (4) counting tasks (e.g., number of characters, number of morphological tags).

(1) Morpho-syntactic/semantic tasks

Case Marking

161 out of 261 languages express the syntactic and semantic relationship between the nominal constituents and the verbs via morphological case markers according to Iggesen, 2013. For instance, in the sentence: “Mark broke the window with a hammer”, “window” and “hammer” would be marked with an accusative and instrumental markers respectively for many languages. The relation between case markers and NLP tasks such as semantic role labeling, dependency parsing and question answering have been heavily investigated and using case marking as feature has been shown beneficial for numerous languages and tasks.

Others

For multilingual examples and detailed motivation, please refer to the original paper. Here is a short table showing the relationship between probing tasks and some NLP applications where they could be helpful:

| Task | Example NLP Applications |

|---|---|

| Gender | Dependency Parsing, Coreference Resolution, Essay Correction… |

| Mood | Natural Language Inference (NLI), User intent identification in dialogue systems… |

| Number | Similar to Gender, where “aggreement” is an important measure |

| Universal POS | Almost all applications |

| Person | Dependency Parsing, Coreference Resolution and many other Natural Language Understanding (NLU) tasks |

| Polarity | Sentiment analysis, NLI, other high level NLU |

| Possession | High level NLU tasks |

| Tense | NLI, high-level NLU tasks e.g., coherence, QA |

| Voice | Dependency Parsing, Semantic Role Labeling… |

(2) Pseudowords/Nonwords

These are the artificial words that are phonologically well-formed but have no meaning. They are commonly used in psycholinguistics to study lexical choices or different aspects of language acquisition. (Some English pseudowords generated by Wuggy: atlinsive, delilottent, foiry.) This test can be used to especially distinguish subword-level models that can capture semantic-level information from the ones that remain on ortography-level. A model that can capture semantics would be expected to distinguish pseudowords from distionary words—given that the vocabulary is composed of subword units.

(3) Comparative Tasks

Odd Feat

We prepare pairs of surface forms which differ only by one feature value and label them with this odd feature. For instance the Spanish token pairs “legalisada” (Verb, Singular, Participle, Feminin) and “legalisado” (Verb, Singular, Participle, Masculin) will have the label Gender.

Same Feat

Similarly, surface forms pairs which share only one feature are labeled with the common feature.

Although these contrastive features are not directly linked to any simple linguistic property, they can be valuable assets to compare/diagnose models for which it is important to learn the commonalities/differences between a pair of tokens, such as natural language inference.

(4) Counting Tasks

Tag Count

It contains tuples of surface forms and the number of morphological tags they have. For instance the Turkish word “deneyimlerine” (to their/his/her/your experiences) annotated with (N.DAT.PL.POSS2SG) would have the tag count of 4, while “deneyimler” (experiences) annotated with (N.DAT.PL) would have the count 3. It can be considered a simplistic approximation of the morphological information encoded in a word. It can also be associated with the model’s capability of segmenting words into morphemes, i.e., morphological segmentation.

Character Count

The motivation behind this feature is to use number of characters as an approximation to number of morphological features, similar to Tag Count test. This should be possible for agglutinative languages where there is one-to-one mapping between morpheme and meaning, unlike the mapping in fusional languages. It can therefore be seen as a rough approximation of Tag Count with the advantage of being able to expand this resource to even more languages since it does not require any morphological tag information.

Creating the Tasks: Type-Level and Token-Level

While searching for a dataset to source the probing tests from, the number of languages this dataset covers is of key importance. Although there is only a small number of annotated truly multilingual datasets such as Universal Dependencies, unlabeled datasets are more abundant such as Wikipedia and Wiktionary. For type-level probing tasks, we use UniMorph 2.0 (Kirov et al. 2018).

Word forms may have multiple morphological interpretations when taken out of context. For instance the German lemma “Teilnehmerin” would be inflected as “Teilnehmerinnen” as a plural noun marked either with accusative, dative or a genitive case marker. We remove such words with multiple interpretations for the same feature. In total, we have created 15 probing tests for 24 languages, each containing 7K training, 2K development and 1K test instances.

Type-level probing has several advantages: it’s compact and less prone to majority and domain shift effects. However, it limits the evaluation of contextualized word representations and black-box models. To address this, we also prepare a set of comparable token-level probing tasks using Universal Dependency Treebanks annotated with Unimorph Scheme.

Comparing Type-Level and Token-Level Tasks

Properties and quality of the probing tasks are strongly tied to the properties and the quality of resources used while creating them. In short, we find the following six aspects of the resource crucial for the probing task quality: (1) dataset size, (2) data domain and token frequency, (3) data quality, (4) lexical variety, (5) ambiguity and (6) use cases.

Dataset size

The agglutinative languages, generally have higher amount of instances for type-level tasks than token-level tasks, due to their productive morphology. The trend is opposite for fusional languages—also related to the fact that most of them being high-resource languages.

Data domain and token frequency

Type-level tasks are induced from a dictionary based resource (Wiktionary), while token-level tasks are based on existing language-specific treebanks. Token-level tasks based on running text are inevitably biased to the domain of this text, while type-level probing tasks are expected to be domain-neutral. In particular, dictionary-based tasks do not contain any frequency information of the surface forms, while token-level tasks do. Although the frequency information may be helpful in some cases, e.g., when the domains of the downstream tasks and the probing tasks are similar, it would also add a bias regarding the distribution of specific features. A token-level test would be penalized less for misclassifying rare forms, and the probing classifier might benefit from using majority class information which might depend on the domain (e.g., singular nouns are more frequently observed than plural nouns).

Data quality

We refer to the labeling accuracy of the datasets used. It is similar for both tasks.

Lexical Variety

For type-level tasks, not all lexical classes can be presented for all languages. For instance, Spanish only has verb inflections that limit the scope of probing. On the other hand, treebanks are based on running text in which all lexical classes are represented.

Ambiguity

For agglutinative languages, where we have one-to-one morpheme to meaning mapping, the ambiguity ratios for both tasks are lower. For fusional languages the ambiguity ratios are higher, mostly due to syncretism, however since the tokens are provided within the context, it enables models to resolve the ambiguity.

Use cases

From the representation perspective, type-level tasks are better suited for probing context-free word embeddings (i.e., static or subword-level); while token-level tasks are more suitable for contextual embeddings (due to having many duplicate training and test instances when tokens are isolated from context). Token-level tasks can be used as a diagnostic probing tool for any downstream model layer that doesn’t require any additional task-specific inputs (e.g. part-of-speech tags for dependency parsers, predicate flags for SRL). Type-level tasks, on the other hand, are more suited to diagnose the initial word encoding layer that generate a type of word representation in isolation; not the intermediate hidden layers that require contextual information.

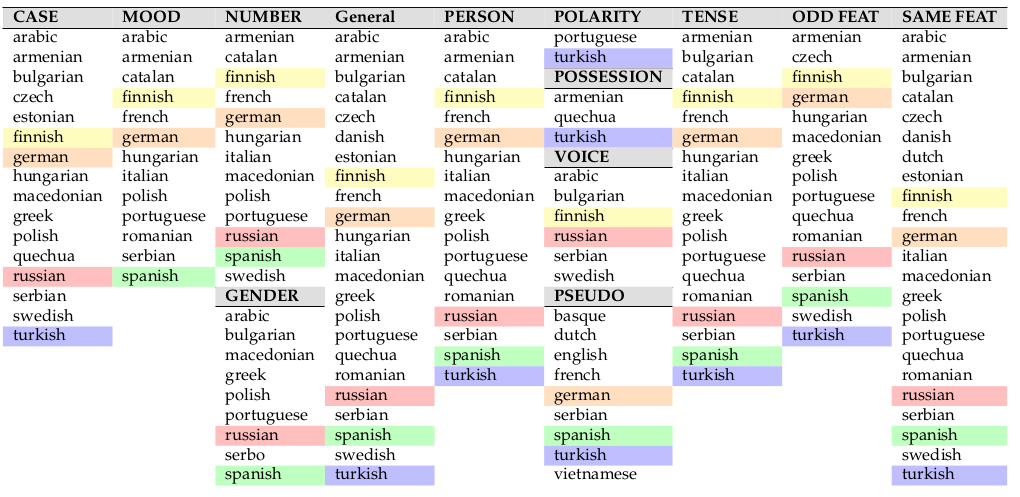

Evaluation Methodology

- Since there are too many languages in our dataset, we first need to choose a meaningful subset of languages to experiment on. There are three questions we ask before we include the language: (1) Does it have enough labeled downstream data for correlation study? (2) Does including the language increase the number of probing tasks in our experiments? (3) Is it typologically different from the other chosen languages? Considering these criteria, the languages we chose are colored in the table below.

- Next, we choose a set of multilingual embeddings for the experiments. Aggarwal et. al., 2016 discuss the importance of having diverse samples for a credible correlation study. The reason is not to have homogeneous clusters among the sampled data points. Considering this, we use models with different objectives, architectures or units: word2vec, fasttext, GloVe-BPE, MUSE and ELMo.

- The embeddings are then evaluated on all combinations of chosen languages and probing tasks.

- Similarly, they are then evaluated on all combinations of chosen languages and downstream tasks, which are chosen as POS-tagging, dependency parsing (DEP), named entity recognition (NER), Semantic Role Labeling (SRL) and cross-lingual Natural Language Inference (XNLI).

- Finally, we check the Spearman correlation between probing task scores and downstream tasks scores:

Findings

In the paper, we discuss numerous factors except from the neural architectures that play role on the results such as out-of-vocabulary (OOV) rates, domain similarity, statistics of both datasets (e.g., ambiguity, size), training corpora for the embeddings; as well as typology, language family, paradigm size and morphological irregularity. We also provide a detailed list of language-related, downstream task-related findings. Here we only give the main few take-aways of this study for convenience:

- The general ranking of the embeddings according to the probing tasks were: ELMo, fastText/GloVe-BPE and word2vec/MUSE. That hints to the applicability of Scenario 3: using probing task scores as a proxy for a more general quality measure.

- Language specific tests are beneficial, i.e., have significantly higher correlation (e.g., Polarity for Turkish). Some tests are more impactful for a language family (e.g., CharacterCount for agglutinative languages). Some downstream tasks have higher correlation to some probing tasks (e.g., contrastive/comparative tests for XNLI). That hints to the applicability of Senario 2.

- There is a strong connection between the correlated tests and the morphological features captured throughout the epochs of black-box Finnish and Turkish SRL models, suggesting that diagnostics can be a useful application of the probing tasks as in Scenario 1.

- There are commonalities among languages, e.g., Case, POS, Person, Tense and TagCount having a relatively higher correlation compared to other probing tasks in Finnish, Turkish, German and Russian.

- We also find and discuss many factors that add noise to the evaluation study. When number of data points is not enough to reliably estimate the correlation, the noise should be interpreted carefully. Some example factors are:

- Static word embedding spaces (word2vec and MUSE) generally rank higher on downstream tasks compared to probing tasks, due to having lower OOV ratios in downstream tasks. (Shared vocabulary)

- Apart from linguistic properties, dataset statistics play a crucial role on the results (e.g., domain similarity for Finnish; lexical variety for Spanish; low OOV ratio for all XNLI tasks).

Further Links

We release the framework LINSPECTOR with https://github.com/UKPLab/linspector, that consists of the datasets for all probing tasks along with an easy-to-use probing and downstream evaluation suite based on AllenNLP. We also have a web demo, where users can probe their embeddings online: https://linspector.ukp.informatik.tu-darmstadt.de/. We currently support probing of static embeddings (e.g., word2vec, fasttext etc…), HuggingFace Transformer models and some AllenNLP downstream models. The code for the web service is also publicly available at https://github.com/UKPLab/linspector-web.